viewof params = Inputs.form({

T: Inputs.range([0., 4], {label: "Temp.", value: 1.0, step: 0.1,}),

g: Inputs.range([-2, 2], {label: "Tilt", value: 0, step: 0.1}),

reset: Inputs.button("Reset simulation")

})

// Simulation parameters

dt = 0.005

kB = 1

gamma = 1

// Double well potential: V(x) = x^4 - 2x^2 + g*x

V = (x, g) => x**4 - 2*x**2 + g*x

force = (x, g) => -(4*x**3 - 4*x + g)

// Live simulation with temperature control

simulationState = {

let x = 0

let positions = [0]

let step = 0

while (true) {

if (params.reset) {

x = 0

positions = [0]

step = 0

}

let f = force(x, params.g)

let noise = Math.sqrt(2 * kB * params.T * dt / gamma) * (Math.random() - 0.5) * 2

x += (f / gamma) * dt + noise

positions.push(x)

// Keep only last 500 points for performance

if (positions.length > 500) {

positions = positions.slice(-500)

}

yield {x, positions: [...positions], step: step++}

await new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(resolve, 10))

}

}

// Plot

Plot.plot({

width: 700,

height: 400,

grid: true,

x: {domain: [-2.5, 2.5], label: "Position"},

y: {domain: [-2, 3], label: "Potential Energy"},

marks: [

// Potential curve

Plot.line(

Array.from({length: 200}, (_, i) => {

let x = -2.5 + 5 * i / 199

return {x, y: V(x, params.g)}

}),

{x: "x", y: "y", stroke: "red", strokeWidth: 2}

),

// Particle trajectory (trail)

Plot.line(

simulationState.positions.map((x, i) => ({x, y: V(x, params.g), step: i})),

{x: "x", y: "y", stroke: "blue", strokeWidth: 1, opacity: 0.5}

),

// Current particle position

Plot.dot([{

x: simulationState.x,

y: V(simulationState.x, params.g)

}], {x: "x", y: "y", fill: "blue", r: 6, stroke: "white", strokeWidth: 2})

]

})Complex Disordered Systems

Francesco Turci

Today

- Entropy matters

- Introduction to colloids

Entropy matters

Entropy matters

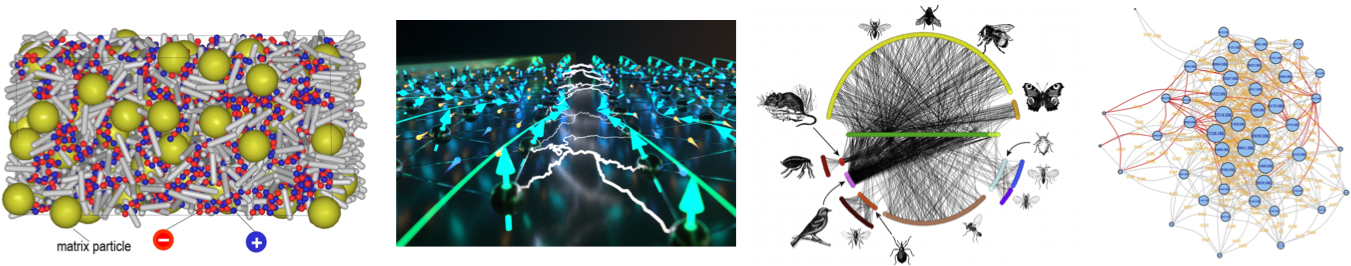

More is different

Philip Anderson (Science 1972)

Complexity emerges when many simple units interact: studying the individual components does not explain the emergence of collective properties

Simple examples:

- phases of matter

- magnetism, superconductivity

- emergence of order from disorder

Also beyond physics:

- formation of biological molecules

- ecological networks

- economic structures (markets, currencies etc.)

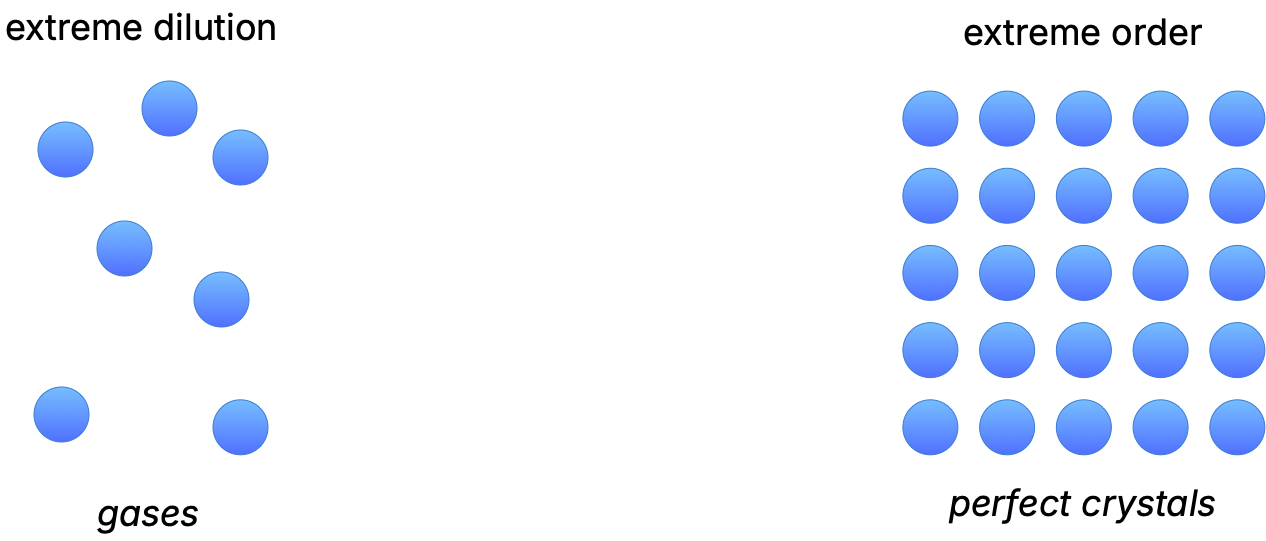

Beyond the usual phases of matter

We sometimes oversimplify…

Extreme examples of phases of matter

Beyond the usual phases of matter

We sometimes oversimplify…

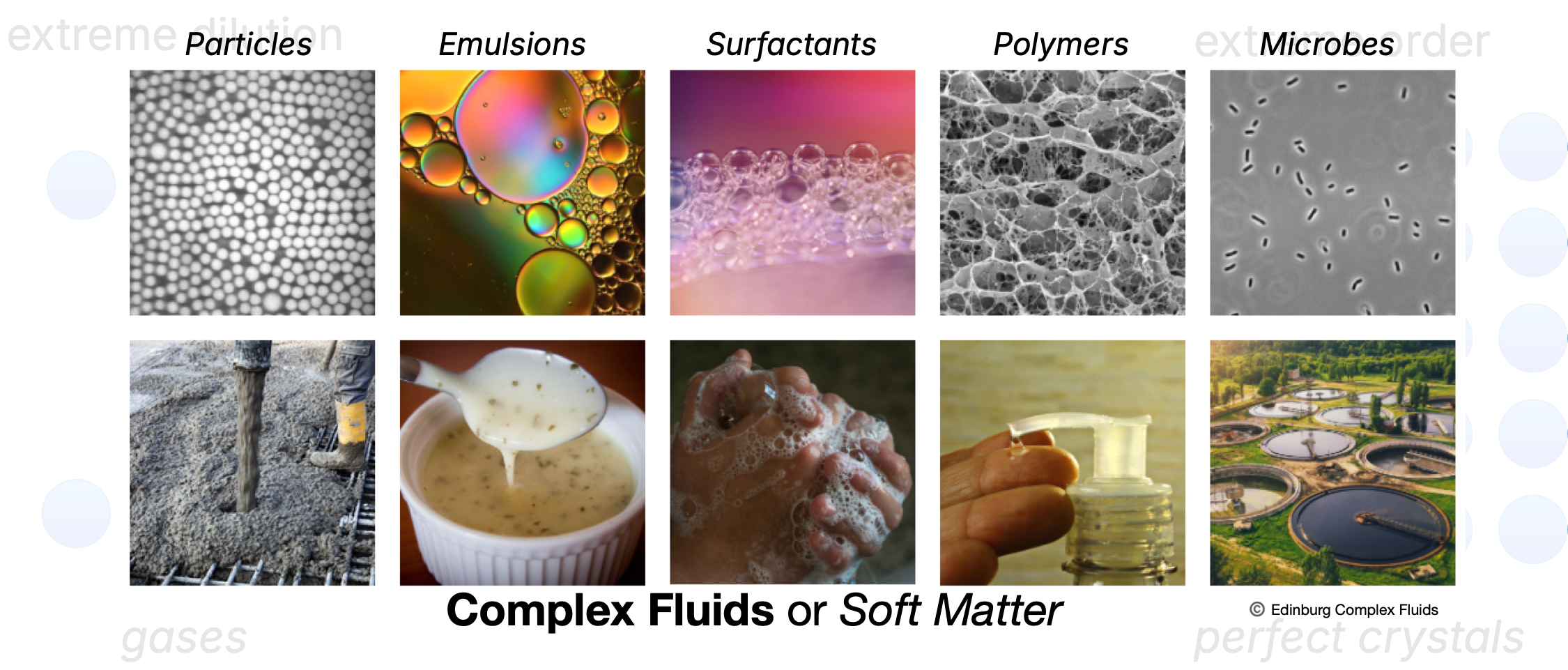

Complex fluids and soft condensed matter

Soft condensed matter includes assembllies of colloids, polymers, surfactants, and biological macromolecules and much more.

- Term due to Pierre-Gilles de Gennes (Nobel 1991)

Often, many ofthese are also referred to as complex fluids.

These materials are easily deformed and show complex, disordered structures.

Their properties are determined by a balance between energy and entropy.

Thermal fluctuations play a major role in their behavior.

Understanding them requires statistical mechanics .

Thermal fluctuations and entropy

Helmholtz Free energy per particle f = u-Ts

Entropy approximately counts the number of arrangements per particle s = \dfrac{k_B}{N} \ln{\Omega}. For hundreds of arrangements per particle one has s=O(1) k_B

Fluctuations of the internal energy are on the same scale as thermal fluctuations: \boxed{\Delta u \sim k_B T} where k_B is the Boltzmann constant and \Delta u indicates standard deviations from the average internal energy.

Thermal fluctuations: single particle in a double well

Systems and definitions

Elementary constituents and energy scales

- Soft matter systems are made of many parts

- The assembly of these many parts can be easily deformed.

- Interactions between these parts are weak compared to thermal or mechanical forces.

Hard condensed matter:

Basic units: atoms

Strong interactions (0.1–10 eV)

Covalent/ionic bonds

Focus on low temperatures

Soft matter:

Basic units: molecular aggregates

Weak interactions (0.001–0.2 eV)

Van der Waals, hydrogen bonds

1 k_B T \approx 0.025 eV (room temperature)

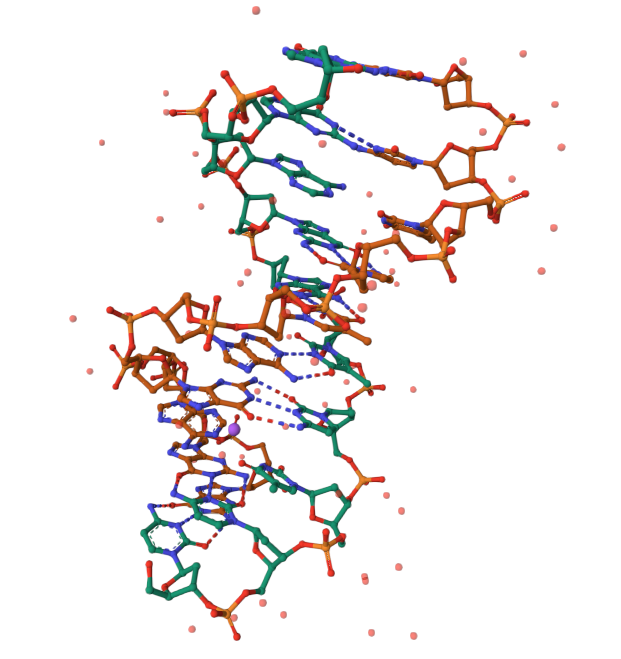

Coarse graining

- Soft matter interactions are mainly electrostatic.

- Atomistic details are often unimportant for macroscopic properties.

- Coarse-graining simplifies models by focusing on key features:

- deliberate selection of what matters

- systematic integration of a number of degrees of freedom

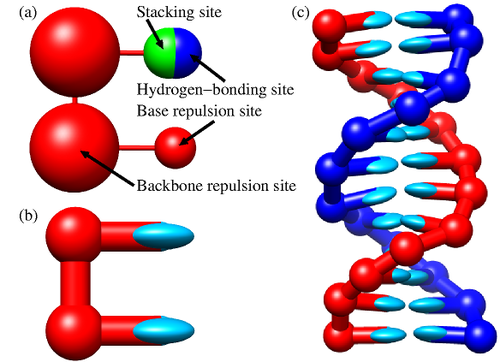

- Example: The oxDNA model represents DNA as a chain of coarse grained units, much larger than the atoms.

Coarse graining

- Soft matter interactions are mainly electrostatic.

- Atomistic details are often unimportant for macroscopic properties.

- Coarse-graining simplifies models by focusing on key features:

- deliberate selection of what matters

- systematic integration of a number of degrees of freedom

- Example: The oxDNA model represents DNA as a chain of coarse grained units, much larger than the atoms.

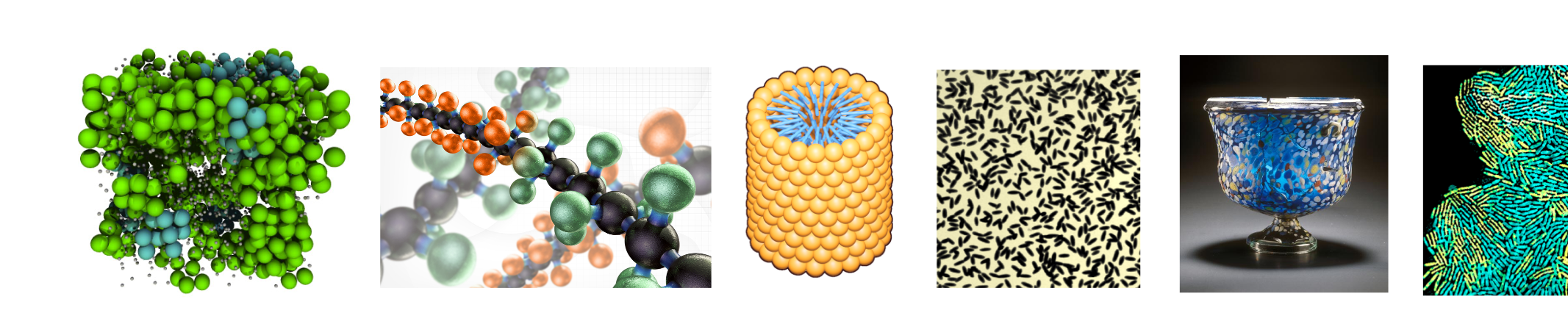

Classes of systems

In our exploration of soft matter we will focus on six main classes of systems which display different physics:

- colloidal dispersions

- polymeric systems

- liquid crystals

- surfactant aggregates

- arrested systems

- active matter

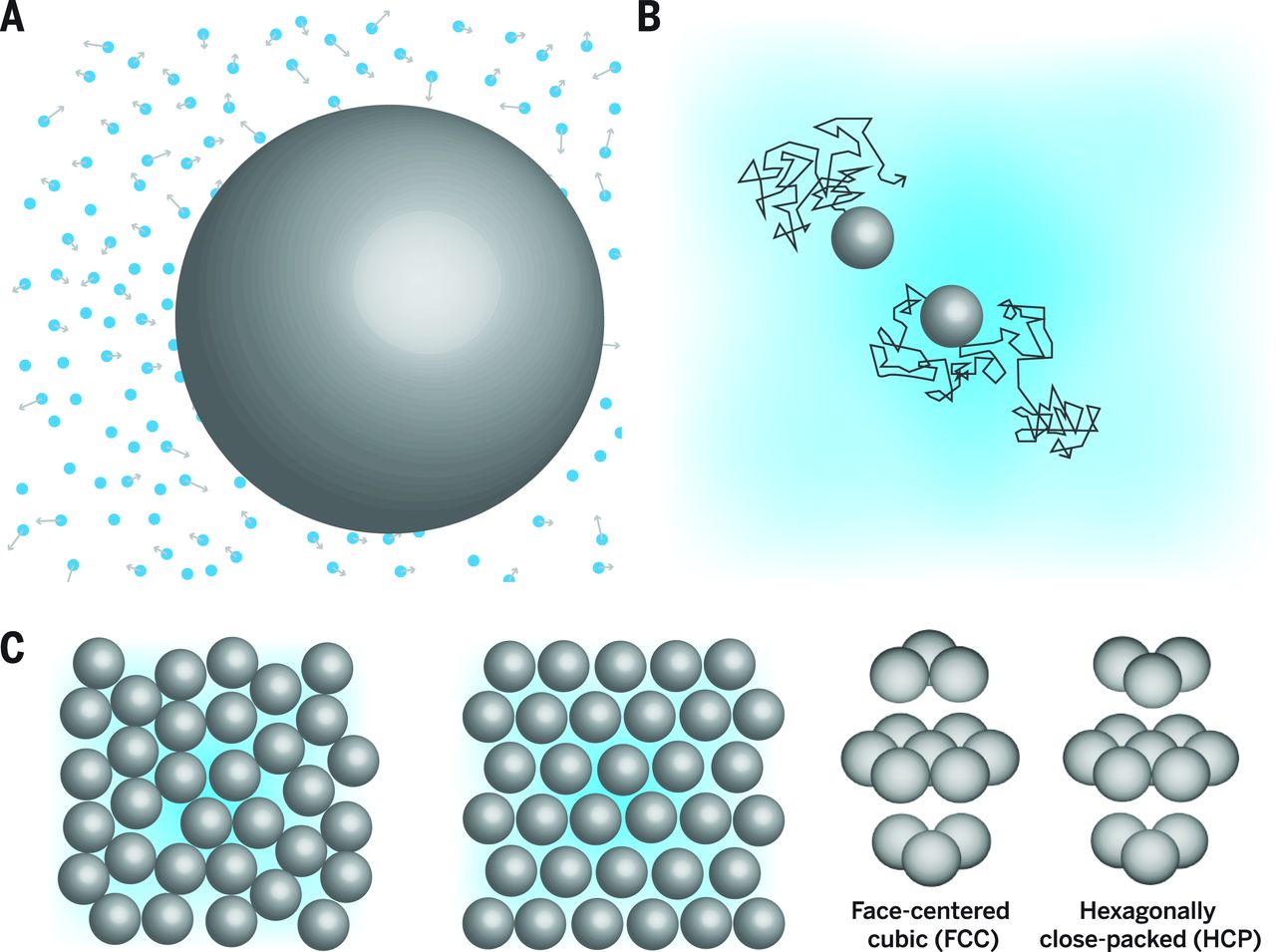

Colloidal dispersions

Colloidal dispersions: small particles (nano–micrometer) suspended in a solvent.

Spherical colloids are common, but many shapes and interactions exist.

Behave as “big atoms”: show Brownian motion, phase transitions, and can form ordered structures.

Larger size and slower dynamics make them ideal for direct observation of phenomena like:

- crystallisation

- glass formation

- gel formation

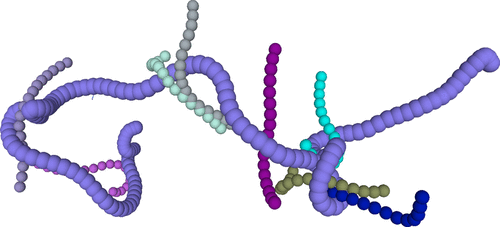

Polymeric systems

- Polymers are long-chain macromolecules made of repeating monomers.

- Their properties result from a balance of entropy and energy.

- Two main types: synthetic polymers (e.g., plastics) and biopolymers (e.g., DNA, proteins).

- Entanglement: chains cannot cross, leading to unique mechanical behavior.

Polymer entanglement, from Likhtman and Ponmurugan, Macromolecules (2014)

Liquid crystals

Liquid crystals form when anisotropic soft matter units (e.g., rod-like or disk-shaped molecules) pack densely, leading to partial order—intermediate between liquids and crystals.

Continuum free energy theories describe liquid crystals by considering the symmetry of their order parameters.

Liquid crystals are crucial in technologies like liquid crystal displays (LCDs).

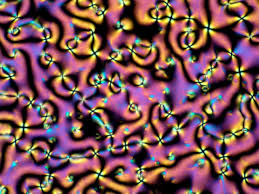

Texture of nematic liquid crystals, from https://doi.org/10.3986/alternator.2020.38

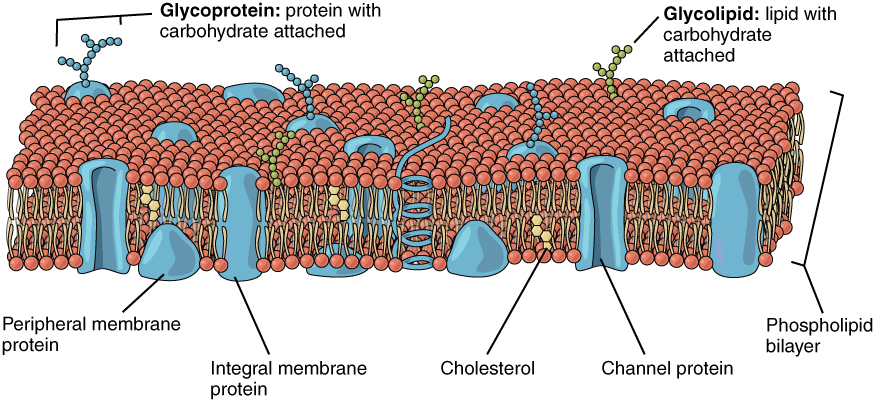

Surfactant aggregates

- Surfactants lower surface tension between fluid phases by accumulating at interfaces.

- They are molecules with both hydrophilic heads and hydrophobic tails.

- Surfactants self-assemble at interfaces, forming structures like bilayers and vesicles.

- These assemblies are essential in cell biology and many soft matter systems.

Cellular membrane

Arrested systems

- Arrested systems are trapped in disordered, non-equilibrium states.

- Lack of long-range order leads to slow structural relaxation and prevents reaching the global energy minimum.

- Examples: glasses and gels

- These systems exhibit rigidity, elasticity, and plasticity: disordered (semi)-solids.

- Relaxation times are longer than observable timescales, making equilibrium statistical mechanics insufficient.

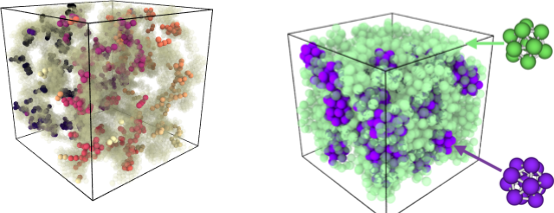

An gel (left) and a glass (right) from molecular dynamics with local structure highlighted un colours

Active matter

- Active matter: systems of units that consume energy to move or exert forces.

- Inherently out of equilibrium due to continuous energy input.

- Includes biological systems (bacteria, cells, flocks) and synthetic systems (self-propelled colloids).

- Shows emergent collective behaviors: swarming, clustering, pattern formation.

- Studied using hydrodynamic theories and agent-based models.

Example of active systems, from Cichos et al. Nature Machine Intelligence (2020)

Introduction to Colloids

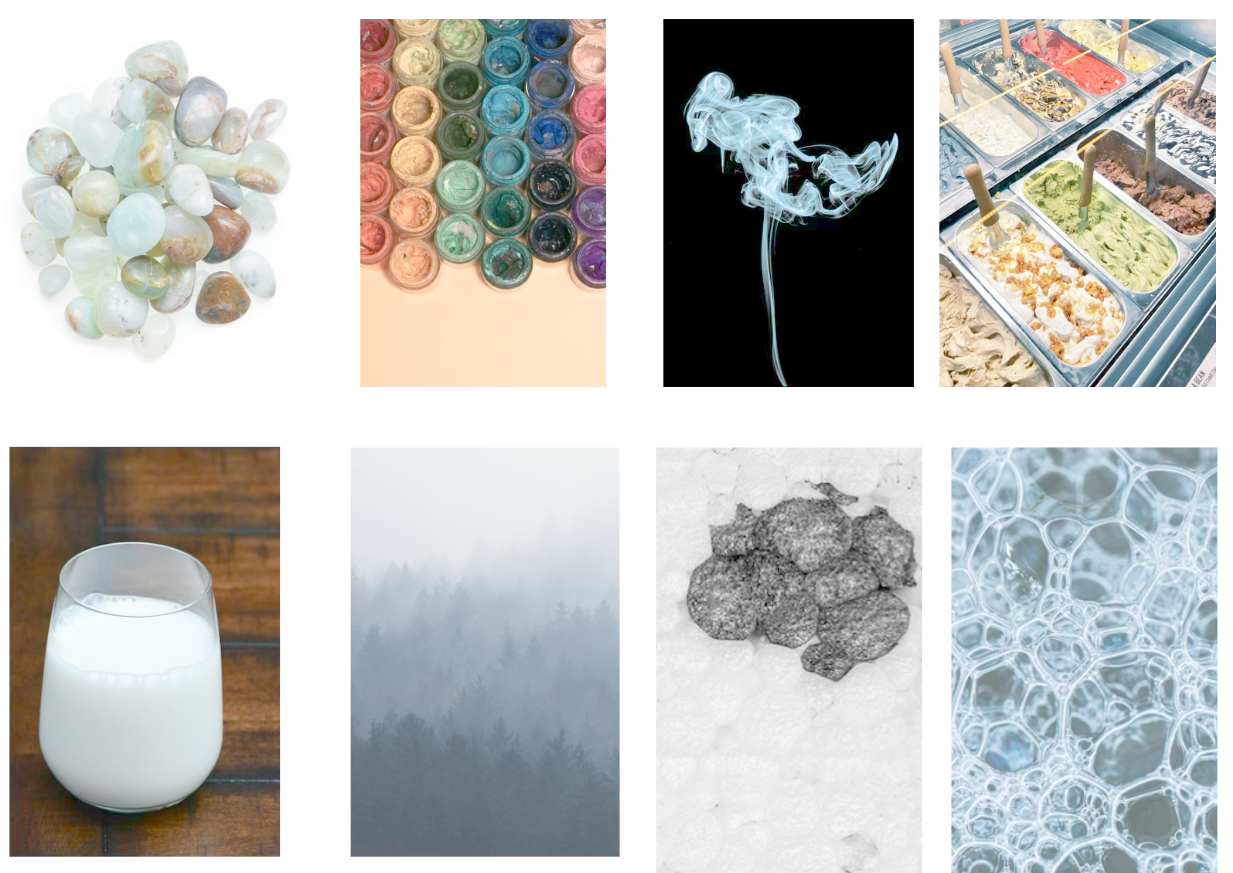

Kinds of colloids

- Colloids = dispersed phase + dispersion medium

Kinds of colloids

| Dispersion Phase | Dispersion Medium | |

|---|---|---|

| Solid | Liquid | |

| Solid | Solid suspension: pigmented plastics, stained glass, ruby glass, opal, pearl |

Sol, colloidal suspension: metal sol, toothpaste, paint, ink, clay slurries, mud |

| Liquid | Solid emulsion: bituminous road paving, ice cream |

Emulsion: milk, mayonnaise, butter, pharmaceutical creams |

| Gas | Solid foam: zeolites, expanded polystyrene, ‘silica gel’ |

Foam: froths, soap foam, fire-extinguisher foam |

IUPAC definition

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines

colloidal: The term refers to a state of subdivision, implying that the molecules or polymolecular particles dispersed in a medium have at least in one direction a dimension roughly between 1 nm and 1 \mum , or that in a system discontinuities are found at distances of that order.

Note

The definition has little to do with the chemistry of the polymolecules (i.e. aggregates), but essentially is determined by the size.

- Why the size?

Colloidal scale

- Particle of size R (micrometric) in medium with constant collisions at thermal energy \sim 1 k_B T

- Compare the energy with the potential energy of settling over a length R

- Obtain a nondimensional number the gravitational Péclet number

\mathrm{Pe}_g=\frac{\Delta m g R}{k_B T}

Example

For a milk protein particle (casein micelle) in water:

- R \sim 0.5 \, \mum (estimate)

- \Delta m = \frac{4}{3}\pi R^3 \Delta \rho \sim \frac{4}{3}\pi (0.5 \times 10^{-6})^3 \times 200 \sim 1 \times 10^{-16} kg (assuming \Delta \rho \sim 200 kg/m³)

- g = 9.8 m/s²

- k_B T \sim 4 \times 10^{-21} J (room temperature)

\mathrm{Pe}_g = \frac{1 \times 10^{-16} \times 9.8 \times 0.5 \times 10^{-6}}{4 \times 10^{-21}} \sim 0.1

Since \mathrm{Pe}_g < 1, thermal motion dominates gravity → particles remain suspended → stable colloid!

Observation time and stability

Any measurement in physics has an observation time t_{\rm obs}

Thermal systems have some degree of memory and hence an intrinsic timescale \tau (relaxation time)

When \tau\ll t_{\rm obs} we can take time-averages and consider the system in a stable steady state.

In the absence of net currents, this is an equilibrium state

A colloidal dispersion is stable if it is able to remain dispersed and Brownian time much longer than t_{\rm obs}.

Instability leads to aggregation

Destabilisation

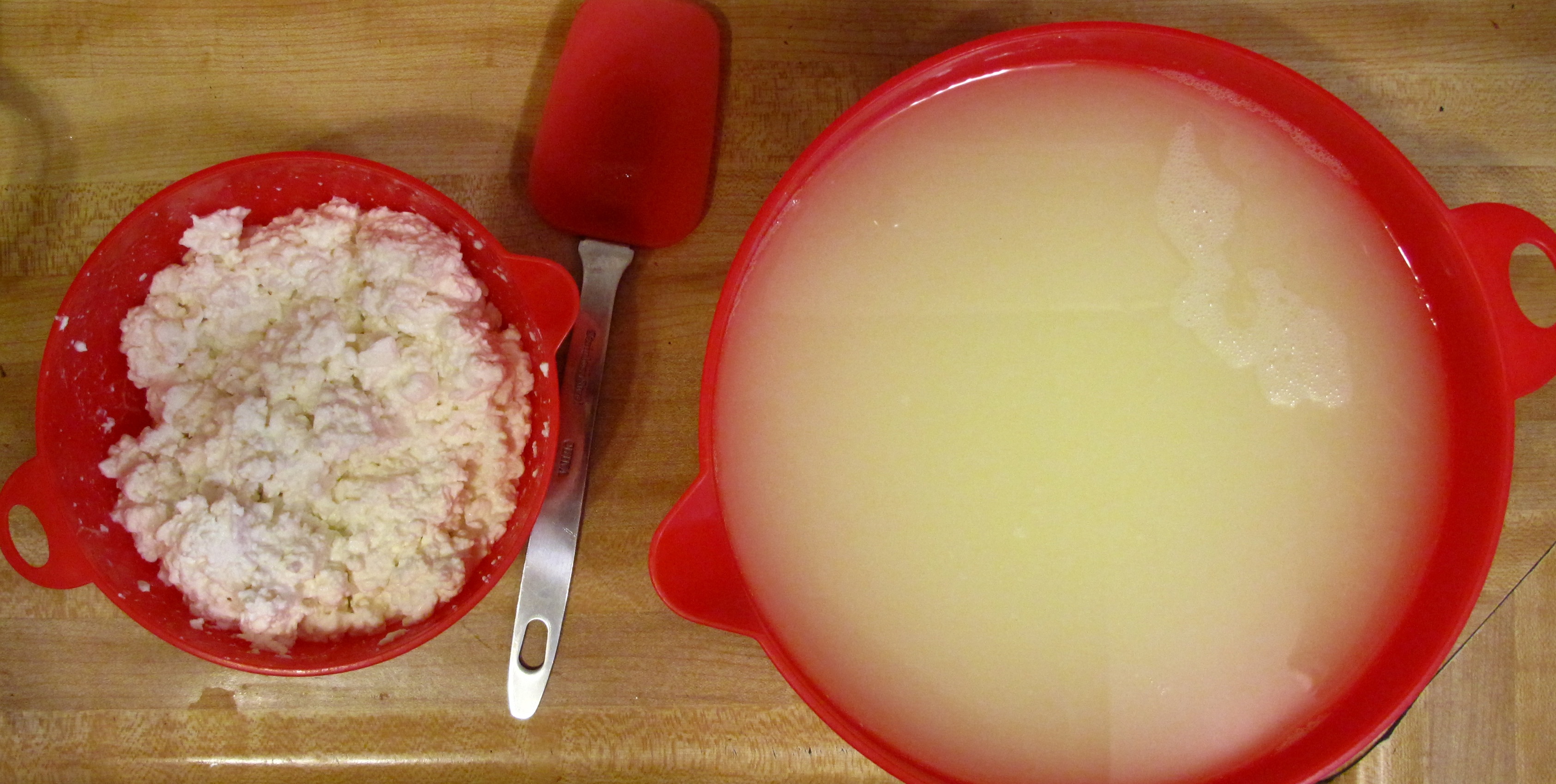

Milk is an emulsion where droplets of fat are dispersed in water and stabilised by proteins.

If lemon juice is added, the dispersion medium (water) changes, the pH drops, and the emulsion is destabilised.

The interactions change → separation of curds (solid) and whey (liquid).

Curds and whey resulting from the destabilisation of milk, a colloidal emulsion. (Wikimedia)

Which interactions?

- At the colloidal scale: gravity and electrostatics (eventually magnetostatics).

- Electrostatics forces are the main microscopic forces: colloids are typically charged

- Separation of length and timescales: colloids are much larger and slower than the atomic or molecular constituents of the surrounding fluid.

- Colloid–colloid interactions result from the collective effect (sum or average) of many microscopic interactions, evaluated over times much longer than microscopic relaxation times.

- When we focus on colloidal scales, we integrate out the microscopic degrees of freedom (coarse-graning)

- Coarse-grained interactions are then obtained and are called effective interactions.

- Fundamental forces:

- gravity

- electro (magneto) static forces

- Effective forces

- Van der Waals forces

- electrostatic repulsion (DLVO)

- depletion forces

- hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions

- steric forces