Complex Disordered Systems

Surfactants

Francesco Turci

Hydrophobicity and amhiphiles

Water is the standard solvent for a lot of chemistry and (almost all) biology.

Molecules in water can be classified by their affinity to water:

- Hydrophilic (“water-loving”) molecules interact favorably with water (e.g., via hydrogen bonding or dipole interactions).

- Hydrophobic (“water-fearing”) molecules do not interact favorably with water (e.g., non-polar molecules).

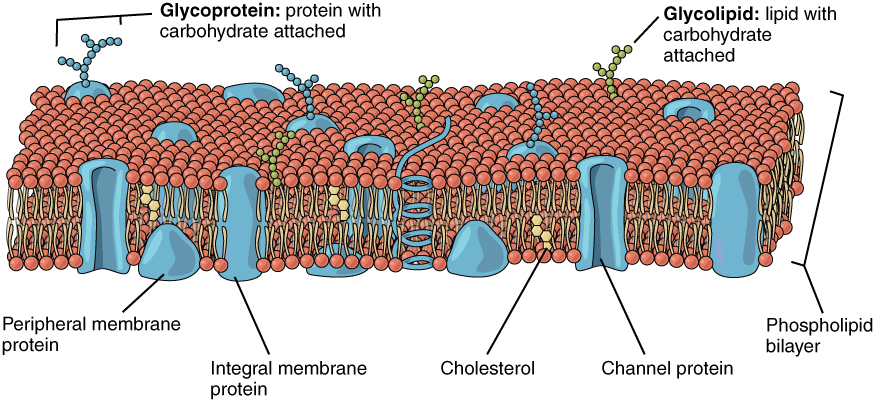

Amphiphiles are molecules that contain both hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts. They include:

- Surfactants (detergents, soaps, SURFace ACTive AgeNT)

- Lipids (cell membranes)

- Some proteins (with hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids)

Schematic model of a surfactant

Hydrophobicity and amphiphiles

Phospholipid bilayers form the cellular membranes. They self-assemble!

Hydrophobicity in brief

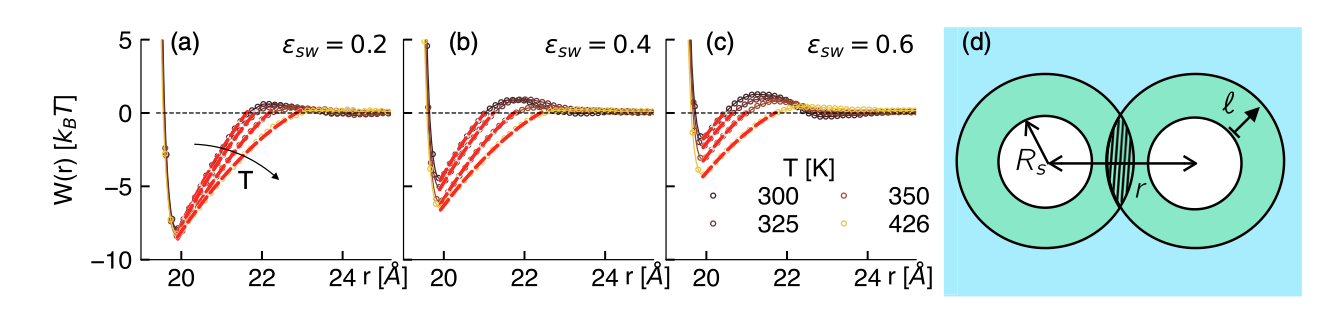

The hydrophobic interactions is a topic of active research.

Various approaches

- (from to 1950s) structural approach: water forms cages around molecules. When the cage is disrupted, entropy increases. Solutes come together to minimise the disruption.

- (from 2000s) interfaces approach: water is a fluctuating medium. Large hydrophobic solutes create interfaces that suppress fluctuations. Solutes come together to minimise the interface area.

- (current research) avoided criticality: water is close to a liquid-vapour critical point. Local curvature and interactions promote large density fluctuations. Solutes interact on scales controlled by these fluctuations.

Effective hydrophobic interactions between spherical solutes of variable solute-solvent affinities \varepsilon_{sw}. A depletion-like construction produces a surface tension-controlled interaction. from Wilding & Turci PRR (2025)

In all cases, the hydrophobic effect originates in fluctuations of the solvent, i.e. the way the solvent explores the available configuration.

Self assembly of surfactants

Code

// This is ObservableJS code

// You can run at observableehq.com or convert it to an equivalent (and faster?) Python version if you like

viewof simulation = {

// --- Parameters ---

const width = 40, height = 40;

const chainLength = 3;

const chainsToCreate = numChains;

const T = temperature;

// const numChains = 10;

const E_TS = 1.0; // tail-solvent energy (solvophobic)

const E_HS = -1.5; // head-solvent energy (solvophilic)

// const T = 0.1; // temperature (kT units)

// --- Initialize grid and chains ---

let grid = Array.from({length: width}, () => Array(height).fill(null));

let chains = [];

// Periodic boundary helper

function mod(n, m) { return ((n % m) + m) % m; }

function getNeighbors(x, y) {

return [

{x: mod(x - 1, width), y: y},

{x: mod(x + 1, width), y: y},

{x: x, y: mod(y - 1, height)},

{x: x, y: mod(y + 1, height)}

];

}

function placeChains() {

for (let id = 0; id < numChains; id++) {

for (let tries = 0; tries < 100; tries++) {

let x = Math.floor(Math.random() * width);

let y = Math.floor(Math.random() * height);

if (grid[x][y]) continue;

let chain = [{x, y, type: 'head'}];

grid[x][y] = {id, type: 'head'};

let ok = true;

for (let i = 1; i < chainLength; i++) {

let last = chain[chain.length - 1];

let nbs = getNeighbors(last.x, last.y).filter(p => !grid[p.x][p.y]);

if (nbs.length === 0) { ok = false; break; }

let next = nbs[Math.floor(Math.random() * nbs.length)];

chain.push({...next, type: 'tail'});

grid[next.x][next.y] = {id, type: 'tail'};

}

if (ok) { chains.push({id, segments: chain}); break; }

else { chain.forEach(p => grid[p.x][p.y] = null); }

}

}

}

function energy(seg) {

let solventNbs = getNeighbors(seg.x, seg.y).filter(p => !grid[p.x][p.y]).length;

return seg.type === 'head' ? solventNbs * E_HS : solventNbs * E_TS;

}

function attemptMove(chain) {

const forward = Math.random() < 0.5;

const tail = forward ? chain.segments[0] : chain.segments.at(-1);

const head = forward ? chain.segments.at(-1) : chain.segments[0];

const options = getNeighbors(head.x, head.y).filter(p => !grid[p.x][p.y]);

if (options.length === 0) return;

const next = options[Math.floor(Math.random() * options.length)];

const dE_old = energy(tail);

grid[tail.x][tail.y] = null;

const dE_new = energy({...next, type: tail.type});

grid[tail.x][tail.y] = {id: chain.id, type: tail.type};

const deltaU = dE_new - dE_old;

const accept = deltaU < 0 || Math.random() < Math.exp(-deltaU / T);

if (accept) {

grid[tail.x][tail.y] = null;

grid[next.x][next.y] = {id: chain.id, type: tail.type};

if (forward) {

chain.segments.shift();

chain.segments.push({...next, type: tail.type});

} else {

chain.segments.pop();

chain.segments.unshift({...next, type: tail.type});

}

}

}

// --- Visualization ---

const svg = d3.create("svg")

.attr("viewBox", `0 0 ${width} ${height}`)

.style("width", "400px")

.style("height", "400px")

.style("border", "1px solid #ccc");

const g = svg.append("g");

function draw() {

const data = chains.flatMap(c => c.segments);

g.selectAll("circle")

.data(data, d => `${d.x}-${d.y}`)

.join("circle")

.attr("cx", d => d.x + 0.5)

.attr("cy", d => d.y + 0.5)

.attr("r", 0.45)

.attr("fill", d => d.type === "head" ? "blue" : "red");

}

// --- Main Loop ---

placeChains();

draw();

let running = true;

const button = html`<button>⏸ Pause</button>`;

button.onclick = () => {

running = !running;

button.textContent = running ? "⏸ Pause" : "▶ Resume";

};

(async () => {

while (true) {

if (running) {

for (let i = 0; i < chains.length; i++) {

const c = chains[Math.floor(Math.random() * chains.length)];

attemptMove(c);

}

draw();

}

await new Promise(r => setTimeout(r, 50));

}

})();

return html`<div>${button}<br>${svg.node()}</div>`;

}Self assembly of surfactants

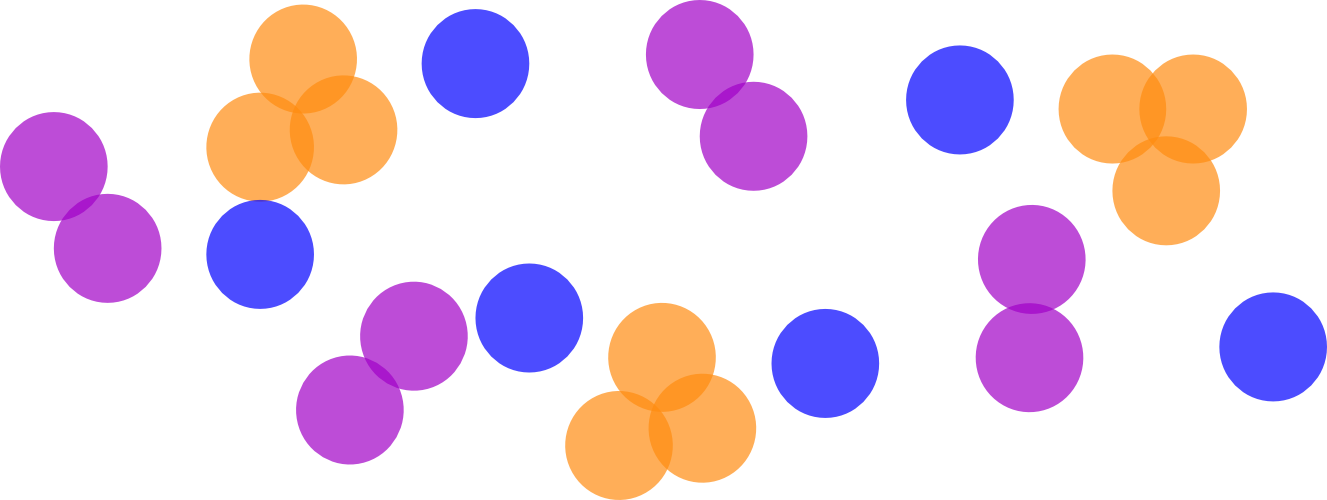

Surfactants are at the molecular scale so they are nanometer sized

- Diffusion is fast (e.g. use D=\frac{k_B T}{6 \pi \eta R} to compare a colloid to a surfactant molecule)

- \to quickly explore possible conformations and minimise free energy.

The amphiphilic structure means that special orientations can be achieved to satisfy the energetic constraints.

The molecules spontaneously form structures: this is called self-assembly.

Underlying phase transitions typically drive the self-assembly.

Aggregation: general case

Consider a generic problem of aggregation of particles (generic)

Simple model: we have cluster of size N and a free energy cost \epsilon_N pto add a particle to the cluster.

Let \mu_1 and \mu_N be the chemical potential of isolated particles and aggregates of size N respectively.

In equilibrium, \mu_1 = \mu_N := \mu

We can express \mu in terms of

- the interaction energy from being in the aggregate \epsilon_N

- the entropy of the aggregate as a whole \propto {\text{ number of aggregates}}\times \ln {\text{ number of aggregates}}

Aggregation: general case

- Let the overall volume fraction to be \phi

- Call X_N the volume fraction in an aggregate of size N, so that \sum_N X_N = \phi.

- The numbers of aggregates of size N per unit volume is then simply X_N/N

Example

- Suppose \phi = 0.1 (10% of the volume is particles).

- Let X_3 = 0.06, X_2 = 0.04 (so \sum X_N = 0.06 + 0.04 = 0.1 = \phi).

- Then the number of trimers is 0.06 / 3 = 0.02 (fraction of solution volume in separate trimer aggregates).

- The number of dimers is 0.04 / 2 = 0.02.

___

The uniform chemical potential is then

\mu = \text{\{energy per particle in aggregate of size N\}} + \text{\{entropy of mixing per particle in aggregate of size N\}}

or \mu = \epsilon_N + \dfrac{k_B T}{N}\ln{\dfrac{X_N}{N}}

Aggregation: general case

From \mu = \epsilon_N + \dfrac{k_B T}{N}\ln{\dfrac{X_N}{N}}

we can rewrite this as

X_N = N \exp{\left( \dfrac{N(\mu-\epsilon_N)}{k_BT}\right)}

and eliminate \mu by evaluating the expression for for N=1 and plugging it back to get

X_N = N X_1^N \exp{\left( \dfrac{N(\epsilon_1-\epsilon_N)}{k_BT}\right)}

The fraction of solutes in the aggregated state is large only if \epsilon_1>\epsilon_N., i.e. there is an energetic advantage.

Aggregation: general case

X_N = N X_1^N \exp{\left( \dfrac{N(\epsilon_1-\epsilon_N)}{k_BT}\right)}

means that knowing the form of \epsilon_N is key to predicting aggregation behaviour.

- Consider an aggregate of N particles of total radius r\approx (Nv)^{1/3} where v is the volume of a single particle.

- Then \epsilon_N is the free energy per particle of the aggregate of size N, G_N/N=\dfrac{1}{N}(\text{ bulk free energy}+\text{surface free energy})

- Assuming that there is a surface free energy cost (a surface tension) \gamma we write

\epsilon_N = \dfrac{G_N}{N} = \epsilon_\infty +\dfrac{1}{N}\gamma r^2 =\epsilon_\infty +\gamma\left(\dfrac{v^2}{N}\right)^{1/3}

which is a monotonically decreasing function of N.

Define \alpha k_B T = \gamma v^{2/3} and extract a relation between X_N and X_1 parametrised solely by \alpha, i.e.

\text{number of aggregates of size N per unit volume} = \dfrac{X_N}{N}\sim (X_1 e^{\alpha})^N

Aggregation: general case

\text{number of aggregates of size N per unit volume} = \dfrac{X_N}{N}\sim (X_1 e^{\alpha})^N This presents us with a few cases depending on \alpha= \gamma v^{2/3}/k_B T

- X_1 e^{\alpha} < 1: Few isolated particles, and (X_1 e^{\alpha})^N becomes vanishingly small for large N

- X_1 e^{\alpha} = 1 (critical point): Aggregates of all sizes become equally probable. The system undergoes phase separation into a dilute phase of isolated monomers (with X_1 pinned at e^{-\alpha}) in coexistence with a dense phase of very large aggregates.

- X_1 e^{\alpha} > 1: Above the critical aggregation concentration, the system cannot remain homogeneous and phase separates. The volume fraction \phi at which this occurs is called critical aggregation concentration, or CAC.

\text{CAC} = X_1^* = e^{-\alpha} = \exp\left(-\frac{\gamma v^{2/3}}{k_B T}\right)

Aggregation: general case

Aggregation: surfactants case

Earlier we assumed that the free energy per particle was \epsilon_N = \epsilon_\infty +\gamma\left(\dfrac{v^2}{N}\right)^{1/3} a monotonically decreasing function of N.

For surfactants, it is not necessarily the case.

- Typically \epsilon_N has a minimum at some finite N=N^* resulting from the fact that beyond a certain size, the aggregate becomes unfavourable (e.g., due to packing constraints, curvature energy, etc).

- Therefore the distribution of aggregates of size N is peaked around N^*.

- This leads to the formation of micelles: aggregates of a characteristic size.

Aggregation: surfactants case

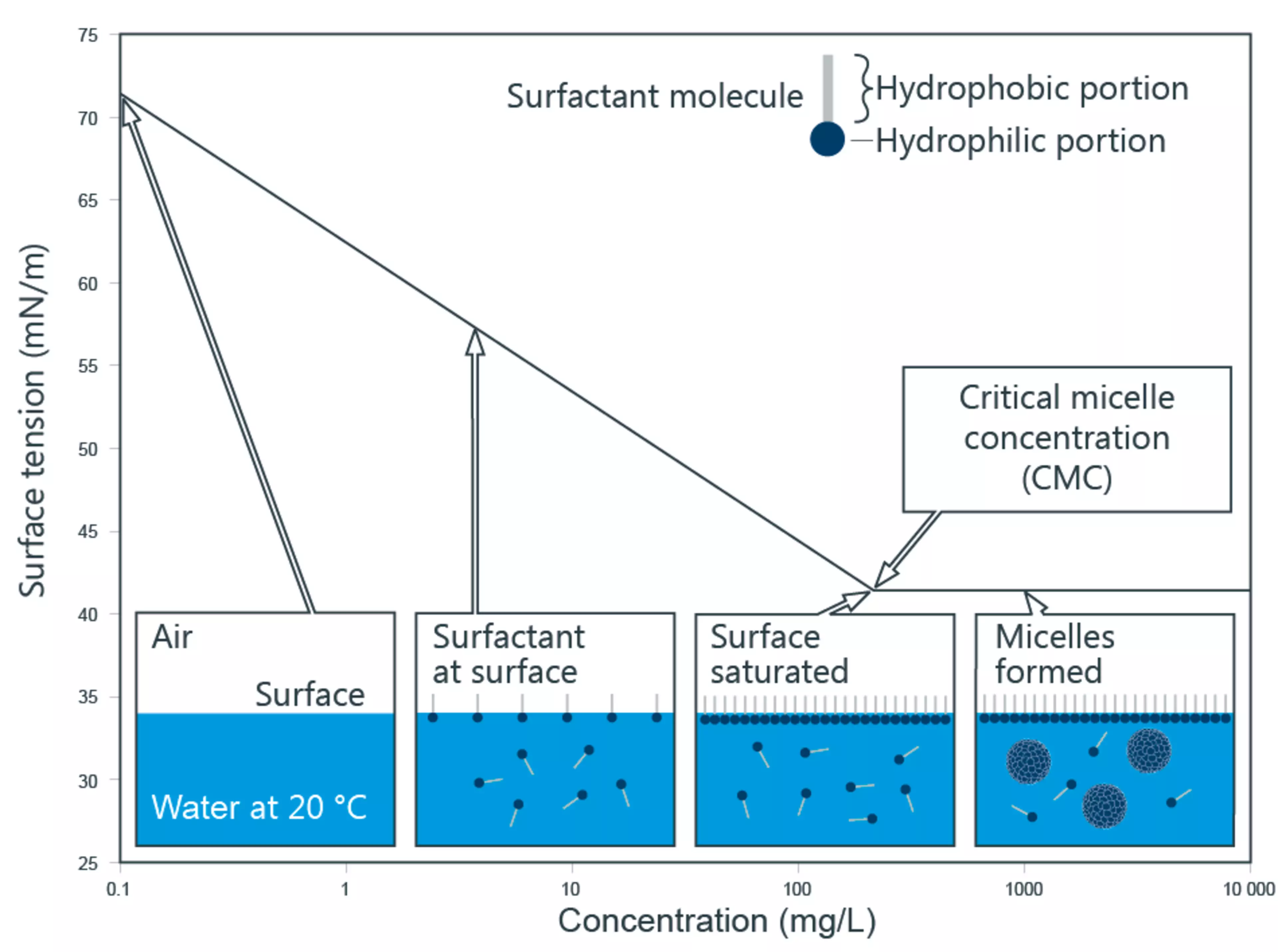

Surfactants in solution: normally, this is done in water in the presence of an interface with air. Due to their nature as amphiphiles, the surfactants typically sit at the air-water interface in a dynamical, equilibrium process that exchanges monomers between the bulk and the surface. The bulk surfactants, when the concentration is larger than a critical value, also self-assemble into micellar structures, which are at equilibrium with the isolated single surfactants.

Critical micellar concentration (CMC)

The addition of surfactants to water initially reduces the water-air surface tension, but when the surface is saturated, further addition leads to crossing the a critical micellar concentration (CMC) and micelle formation.

- Below the CMC, almost all surfactant molecules are present as monomers

- Above the CMC, additional surfactant molecules predominantly form micelles of size N^* while the monomer concentration remains nearly constant.

The aggregation in water follows specific patterns:

- hydrophobic tails cluster together to avoid water

- hydrophilic heads face the water

The structure on the micelle surface (formed by the heads) is disordered and fluid-like, similar to a 2D liquid.

Schematic of micelles (from DataPhysics Instruments).

Critical micellar concentration (CMC)

Surface tension of a surfactant solution with increasing concentration, formation of micelles, from Kruss Scientific

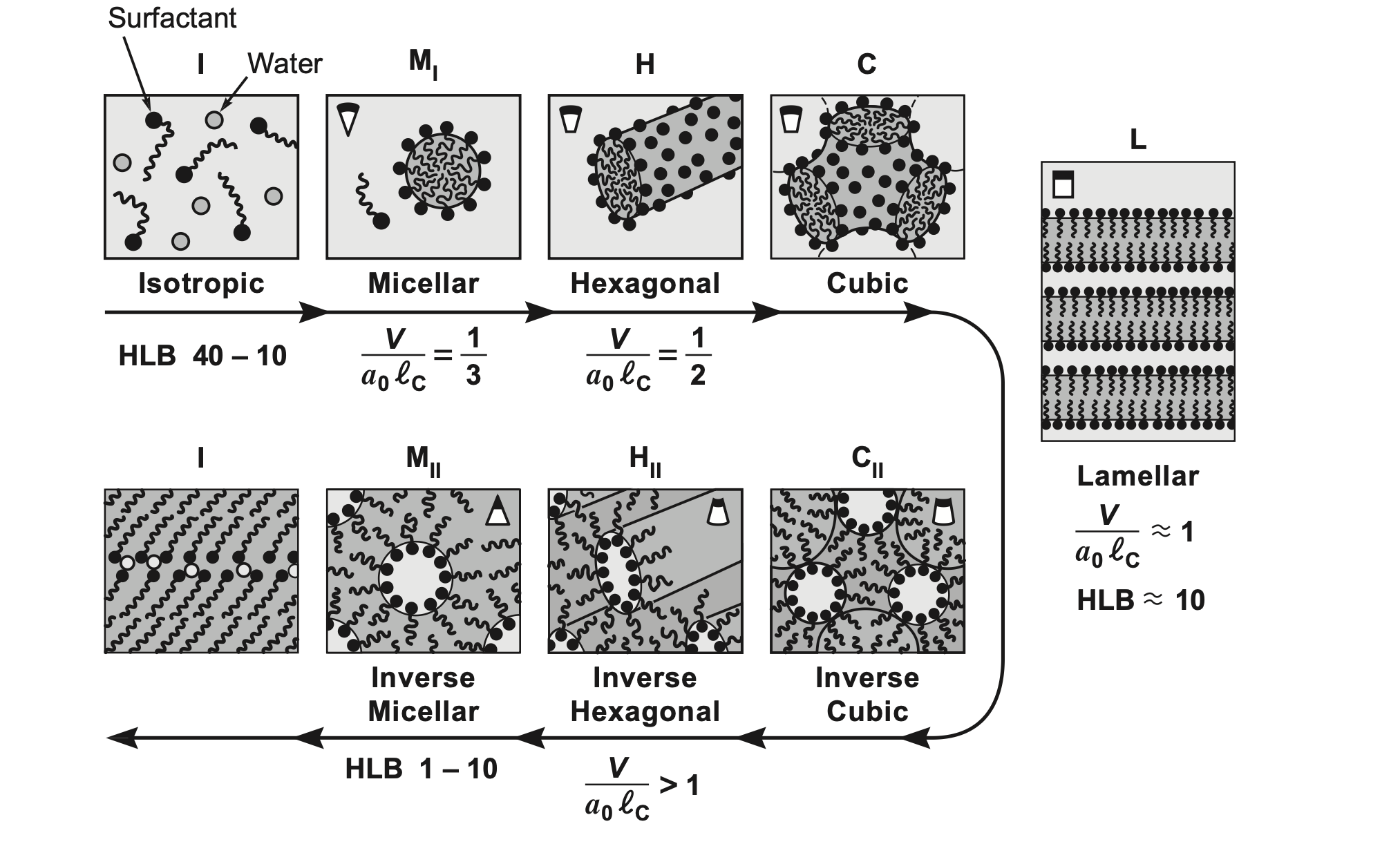

Shape of surfactant assemblies

Geometric model of a surfactant molecule:

- optimal headgroup area a_{0}: depends on chemical structure, pH and temeprature.

- volume v of the hydrophobic part: The hydrophobic part usually consists of hydrocarbon chains. Its volume v\propto n the number of carbon atoms in the chain.

- critical chain length \boldsymbol{l}_{\boldsymbol{c}} : the effective length of the chain, taking into account chain flexibility, temperature, branching and chemical structure. It also scales like l_c \propto n.

A balance between energy and entropy leads to different self-assembled structures .

Different types of self assembled structures: (A) spherical micelles, (B) cylindrical micelles and (C) bilayers.

Spherical micelle

For a spherical micelle of radius R with aggregation number N , the total volume and surface area are given by

\begin{gathered} N v=\frac{4 \pi}{3} R^{3} \\ N a_{0}=4 \pi R^{2}\end{gathered}

Therefore \dfrac{v}{a_{0}}=\dfrac{R}{3}<\dfrac{l_{c}}{3}

where we used the fact that the radius R cannot be larger than the critical chain length \mathrm{l}_{\mathrm{c}}. We thus obtain for the critical packing parameter P

P=\frac{v}{a_{0} l_{c}}<\frac{1}{3}

Cylindrical micelles

For a cylindrical micelle of length L the total volume and surface area are given by N v=\pi R^{2} L

and

N a_{0}=2 \pi R L

Therefore \dfrac{v}{a_{0}}=\dfrac{R}{2}<\dfrac{l_{c}}{2} again using R<l_{C}.

We thus obtain for the critical packing parameter P=\dfrac{v}{a_{0} l_{c}} that \dfrac{1}{3}<P<\dfrac{1}{2}

Below the lower limit spherical micelles are formed.

Bilayers (lamellar)

For a bilayer (with separation D between the layers and area A) the total volume and surface area are given by

\begin{aligned} & N v=A D \\ & N a_{0}=2 A \\ & \frac{v}{a_{0}}=\frac{D}{2}<l_{c} \quad\left(\text { using } D<2 l_{c}\right) \end{aligned}

We thus obtain for the critical packing parameter P=\dfrac{v}{a_{0} l_{c}} that \dfrac{1}{2}<P<1

Below the lower limit cylindrical micelles are formed.

Packing parameter summary

Mesophases formed by surfactants as we vary the packing parameter P=\dfrac{v}{a_{0} l_{c}} , from Israelachvili, J. N., Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd Edition, Academic Press, 2011.