3 The approach to criticality

It is a matter of experimental fact that the approach to criticality in a given system is characterized by the divergence of various thermodynamic observables. Let us remain with the archetypal example of a critical system, the ferromagnet, whose critical temperature will be denoted as \(T_c\). For temperatures close to \(T_c\), the magnetic response functions (the magnetic susceptibility \(\chi\) and the specific heat) are found to be singular functions, diverging as a power of the reduced (dimensionless) temperature \(t \equiv (T-T_c)/T_c\):-

\[ \chi \equiv \frac{\partial M}{\partial H}\propto t^{-\gamma} ~~~~ (H=0) \tag{3.1}\]

(where \(M=mN\)), \[ C_H \equiv \frac{\partial E}{\partial T}\propto t^{-\alpha} ~~~~ (H=\textrm{ constant}) \tag{3.2}\]

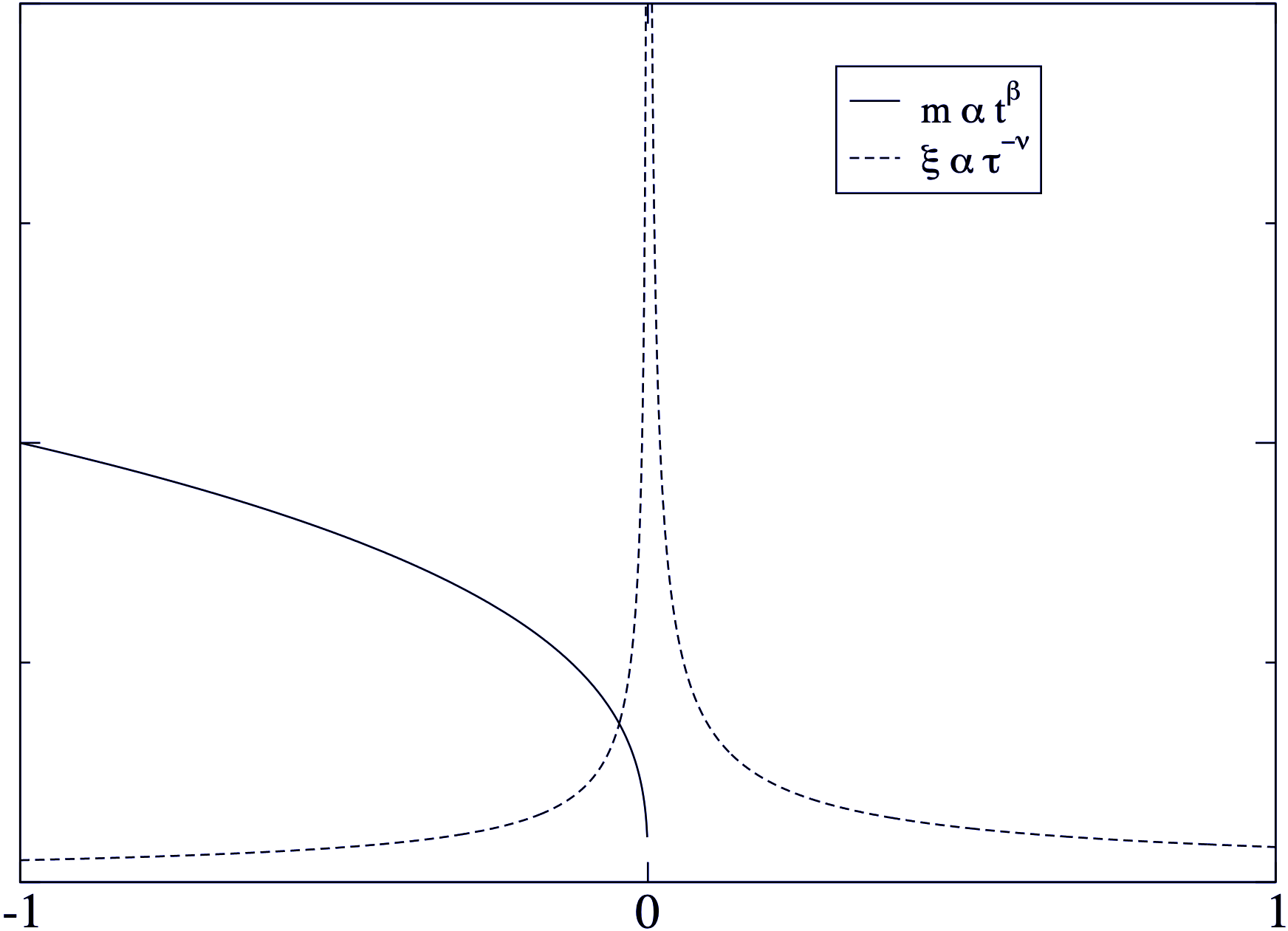

Another key quantity is the correlation length \(\xi\), which measures the distance over which fluctuations of the magnetic moments are correlated. This is observed to diverge near the critical point with an exponent \(\nu\).

\[ \xi \propto t^{-\nu} ~~~~ (T > T_c,\: H=0) \tag{3.3}\]

Similar power law behaviour is found for the order parameter \(Q\) (in this case the magnetisation) which vanishes in a singular fashion (it has infinite gradient) as the critical point is is approached as a function of temperature:

\[ m \propto t^{\beta} ~~~~ (T < T_c,\: H=0) \tag{3.4}\] (here the symbol \(\beta\), is not to be confused with \(\beta=1/k_BT\)– this unfortunately is the standard notation.)

Finally, as a function of magnetic field:

\[m \propto h^{1/\delta} ~~~~ (T = T_c,\: |H|>0) . \tag{3.5}\] with \(h=(H-H_c)/H_c\), the reduced magnetic field (though note that in cases where \(H_c=0\) such as the Ising model considered later, we use instead \(h=H-H_c\)).

As examples, the behaviour of the magnetisation and correlation length are plotted in Figure 3.1 as a function of \(t\).

The quantities \(\gamma, \alpha, \nu, \beta\) in the above equations are known as critical exponents. They serve to control the rate at which the various thermodynamic quantities change on the approach to criticality.

Remarkably, the form of singular behaviour observed at criticality for the example ferromagnet also occurs in qualitatively quite different systems such as the fluid. All that is required to obtain the corresponding power law relationships for the fluid is to substitute the analogous thermodynamic quantities in to the above equations. Accordingly the magnetisation order parameter is replaced by the density difference \(\rho_{liq}-\rho_{gas}\) while the susceptibility is replaced by the isothermal compressibility and the specific heat capacity at constant field is replaced by the specific heat capacity at constant volume. The approach to criticality in a variety of qualitatively quite different systems can therefore be expressed in terms of a set of critical exponents describing the power law behaviour for that system (see the book by Yeomans for examples).

Even more remarkable is the experimental observation that the values of the critical exponents for a whole range of fluids and magnets (and indeed many other systems with critical points) are identical. This is the phenomenon of universality. It implies a deep underlying physical similarity between ostensibly disparate critical systems. The principal aim of theories of critical point phenomena is to provide a sound theoretical basis for the existence of power law behaviour, the factors governing the observed values of critical exponents and the universality phenomenon. Ultimately this basis is provided by the Renormalisation Group (RG) theory, for which K.G. Wilson was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1982.

More about the scientists mentioned in this chapter: